|

|

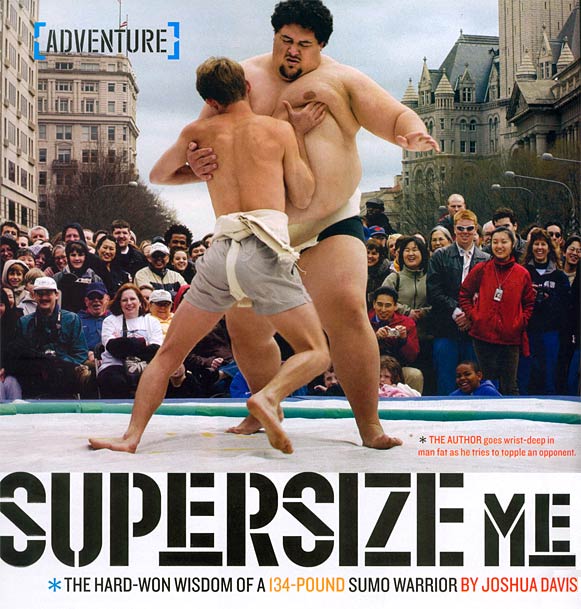

ARCUS BARBER IS READY TO FIGHT. The six-foot-six, 460-pound

amateur sumo star stomps over to one side of the sumo ring in this

Los Angeles hotel ballroom and rests his hands on his prodigious

belly as if it were a card table. This is the first open weight

match of the U.S. Sumo Open and the crowd of nearly a thousand is

excited. They start clapping in unison but suddenly fall silent

when I step forward.

ARCUS BARBER IS READY TO FIGHT. The six-foot-six, 460-pound

amateur sumo star stomps over to one side of the sumo ring in this

Los Angeles hotel ballroom and rests his hands on his prodigious

belly as if it were a card table. This is the first open weight

match of the U.S. Sumo Open and the crowd of nearly a thousand is

excited. They start clapping in unison but suddenly fall silent

when I step forward.

“And on the other side of the ring,” the

announcer purrs through the mike, “at 134 pounds, we have the lightest

man to ever sumo at the U.S. Open….”

I pop in my mouth-guard and trot out to

the ring wearing the mawashi, the classic sumo diaper. The paramedics

in the corner stand up. I can hear murmurs of concern, but almost immediately

the atmosphere starts to change. Though Barber weighs nearly three times

what I do, the audience can sense my confidence; they sense there’s some

other force at play here. And they’re right. I may look skinny, but I’ve

mastered the attitude of a fat man. I lightly slap my wiry stomach, stretch

out my arms and stare blankly at Barber. The crowd starts chanting my

name.

If my opponent is intimidated, he doesn’t

show it. He’s one of North America’s best heavyweight sumo wrestlers and

is known for his stability. He is almost impossible to knock over.

Before stepping forward, I glance to my

left. There’s a 530-pound man sitting next to the announcer. He wears

the distinctive topknot of the professional Japanese sumo wrestler - he’s

not an amateur like Barber and me. His name is Musashimaru, or Maru for

short, and he is widely thought to be one of the best sumo wrestlers of

all time. Though nobody knows it, he is also my coach.

Maru slightly nods at me and I bow to Barber.

We squat in the middle of the ring, and I stare calmly into my opponent’s

round, goateed face. In ten seconds, I will slam violently into his belly

and demonstrate that being fat is a state of mind.

I'M FIVE NINE AND USUALLY weigh less than 130 pounds, but I’ve

always wanted to be a much bigger man. To me, fat is a sign of maturity.

Sumo, I thought, offered me a chance to learn how to be big.

So I showed up at the Jun Chong Martial

Arts Center in West Los Angeles for the California Sumo Association’s

weekly training session. It was a classic karate gym: A dozen kids were

trying to kill each other while their parents looked on approvingly.

“Is sumo time!” announced Svetoslav Binev,

a squat, heavily muscled Bulgarian who is the resident sumo coach. The

kids cleared out, Binev wrapped me in a long canvas strip, briefly went

over the rules, and motioned me into the ring with the founder of the

sumo association, an emaciated-looking 142-pound guy named Andrew.

“Go for his throat,” Binev hinted. “It will

throw him off balance.”

My opponent slapped his belly lazily, as

if it were quite large, though he looked malnourished. Still, I was intimidated.

I didn’t really know what I was doing, but in a moment, Binev shouted

something in Japanese, and Andrew slammed into me. I didn’t have time

to go for his throat, because he already had his hands on my diaper and

was yanking it up. I could feel my balls get cinched, and a wave of anger

swept over me. Suddenly, I started screaming at him in a deep faltering

bass yell. It was a voice I’d never heard before. The voice, perhaps,

of a much fatter man.

Instinctively, I grabbed Andrew’s diaper

and yanked him towards the edge. He did the same to me and we began the

sumo dance that occurs when opponents spin around and around as they try

to hurl each other out of the ring. At the last moment, I pivoted, rolled

him over my belly, and smashed him to the ground. Instinctively, I grabbed Andrew’s diaper

and yanked him towards the edge. He did the same to me and we began the

sumo dance that occurs when opponents spin around and around as they try

to hurl each other out of the ring. At the last moment, I pivoted, rolled

him over my belly, and smashed him to the ground.

“Wow,” Andrew shouted, leaping to his feet.

“That was great.”

“Very nice,” Binev agreed. “You have the

fighting spirit.”

I was coursing with adrenaline. I felt like I had been stripped

down to my most basic self. For the first time in memory, I was

comfortable in my body. I was still skinny but I had moved like

a big man. I had stayed low and used my leverage. I had used my

belly.

“Now we see you and Larry,” Binev said,

nodding at a 285-pound guy in the corner.

Larry lumbered over and bowed. I bowed back

and realized I wasn’t afraid. Larry was at least twice my weight, and

I was prepared to kick his ass.

Binev signaled and Larry lunged. I dodged

left, pivoted and drove into him as hard as I could. He took two small

steps back, recovered and began a 285-pound steamroll toward me. But at

the last minute, I squatted low, grabbed his diaper and rolled him over

my right leg. He landed heavily on his back outside the ring and I came

spinning down on top of him.

“Fantastic,” Binev shouted, slapping me

on the back. And though my beginners luck would soon run out, Andrew told

me that if I trained hard, I had a good shot at medalling in my weight

class at the U.S. Open.

“But first we make you more bigger,” Binev said, tapping my bony

chest. “You get bruised bone otherwise.”

WHEN I GOT HOMEI had trouble breathing. My arms were streaked with

kaleidoscoping yellow and blue bruises and a sneeze hurt so bad I felt

like I was going to pass out. My first afternoon of sumo had wreaked havoc

on me. We had wrestled for two hours, and both of my opponents had begun

consistently beating me by using different techniques. I clearly had a

lot to learn, but the prospect of competing at the U.S. Sumo Open was

thrilling.

I stopped jogging and began eating

as much as I could. I definitely started to feel bigger. Within three

weeks of eating six to seven meals a day, I was up to 132.

I spent every other Sunday training with Andrew, Larry, Binev and

a steady stream of other wrestlers. I could feel my moves improving

I was encouraged by a few wins against the bigger guys though

the bruises on my chest only worsened.

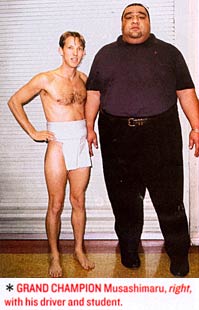

About a month before the U.S. Open, Andrew called me at home. He

sounded a little nervous and explained that one of the guests of

honor for both the National Cherry Blossom Festival in Washington

D.C. and the U.S. Sumo Open in Los Angeles was Musashimaru, aka

Maru. Maru was a Hawaiian who moved to Japan when he was 18 and

rose to become a Yokozuna, a grand champion, a legend in

the world of sumo. And he needed a driver.

A 530-POUND MAN has a strange effect on his environment.

Before Maru pushed through the arrival doors at Dulles Airport,

near Washington D.C., all the light seeping through the edges blacked

out . When the doors opened, an enormous man filled the gap. He

was wearing a velour sweatsuit made by a Japanese street-wear brand

called International Black Brother and was followed by a personal

hairdresser (obligatory company for a Yokozuna), who carried

Maru’s tiny Louis Vuitton backpack. On the bag was a plastic tag

that announced in Japanese that it belonged to the “grand champion.”

I started

bowing immediately. Maru took no notice and kept walking until I introduced

myself as his driver. He seemed amused. His eyebrows naturally angled

up over his brutish face, making him look as if he were perpetually surprised

by how small others were. I started

bowing immediately. Maru took no notice and kept walking until I introduced

myself as his driver. He seemed amused. His eyebrows naturally angled

up over his brutish face, making him look as if he were perpetually surprised

by how small others were.

“You?” he said.

I DIDN'T FULLY appreciate the stature of my passenger until

a few days later, when our SUV was chased for two blocks at the

National Cherry Blossom Festival in D.C. One Japanese guy kept trying

to push his face through the window, and a number of women hoisted

their babies in the air, hoping that Maru would roll down the window

and touch the children for good luck. The Japanese regarded him

as a near deity, but in public he was taciturn, rarely spoke and

never smiled. He was known for his fierceness in the ring and his

reserve outside and seemed to be all the more revered for it.

The grand champion had been

to the mainland United States only once, and he peppered me with questions

about the capital. Unfortunately, I barely knew where we were.

“Here’s

the Washington Monument and the White House and some other stuff,” I said,

sweeping my arm vaguely when we first drove past the Mall.

Maru rolled

down his window and waved at the White House. “Hi Bush,” he sang. “Hi

Bushy bushy bushy!”

“I saw his daddy vomit,” Maru said with a mischievous

smile. He had met three past American presidents and had attended the

infamous dinner when Bush senior threw up. “It wasn’t pretty.”

Maru asked me how I came to be his driver, and I explained that

I was a competitor. From that moment on, he treated me differently.

The very idea of me, the skinny American sumo wrestler, never failed

to bring a smile to his face. He started calling me Bruddah Josh

in his relaxed Hawaiian English and included me in everything he

did. We ate sushi almost every day, and he would order two of everything

on the menu: one for him and one for me.

“We need to put some belly on you,” he’d say, patting his stomach.

“I wish I could give you some of mine. I really want to get down to 400

pounds.”

I was meeting Maru at a difficult time in his life. When a wrestler

achieves the rank of grand champion, he is not allowed to post a losing

record. If he does, he is expected to retire. Maru had broken his wrist,

started losing and, in keeping with the tradition, announced that he was

officially retiring this coming October. He had had one of the fastest

rises through the ranks in sumo history and was only 32, but he already

reminisced like an old man.

“I was so worried when I first got to Japan,”

he said one day over a two-foot long unagi roll. In high school on Oahu,

he had been a football star and was recruited by colleges on the mainland.

But his coach introduced him to a sumo recruiter who offered him a three-month

trial in Japan. Maru wanted to help support his family, so he accepted,

though he knew almost nothing about the sport. But his main concern at

the time was more prosaic: “I just didn’t want to show everybody my butt.”

Maru constantly surprised me. Our first

morning in the car, he shyly asked me what kind of music I liked. When

I said I was open to anything, he pulled out a CD from his Louis Vuitton

backpack. It was a mix of Abba tunes, the Grease soundtrack and Rupert

Holmes’ piña colada song.

Later, in Los Angeles, we visited with Samoan Godfather, the don

of the Boo-Yaa Tribe and the man behind such rap songs as “Bury

U, Bury Me” and “Pimpin', Playin', Hustlin'.” Though he’s not a

big rap fan, Maru befriended the former Los Angeles gang leader

in Japan ten years ago while the Tribe was living in Japan. As I

quietly sat on the couch, the grand champion and the godfather commiserated

about high real estate prices.

“But interest

rates are just too good right now, dawg,” the godfather said.

AT A SUMO demonstration in D.C., Maru informed me that it

was time to work on my tachai, the sumo charge. His hairdresser

helped him into a pair of shorts, and Maru crouched slightly, his

hands on his thighs. Then he instructed me to hit him as if it were

the U.S. Open. The spectators, a bunch of high school students studying

Japanese, were expecting a lecture on the history of sumo. What

they got was me smashing into Maru and recoiling. It felt like colliding

with cement.

“You’re leaping like

a skinny man,” Maru told me. He instructed me to squat lower, advance

my feet and use my weight. “None of this leaping stuff.”

To demonstrate,

he said he would charge me. I took a deep breath. Not many people get

to experience the charge of a grand champion. I readied myself, and he

slammed into me with his head down. The air left my lungs with a whoosh,

and for an instant I was airborne. But I had gained weight, both physically

and mentally, and I landed on the ground with an impressive thud.

“It’s

all about learning how to use your weight,” Maru said.

EGG ROLLS

chicken wings, coleslaw, two whole fish, steak, corn, boiled shrimp, a

vanilla sponge cake and a two-foot tall bowl of layered triple chocolate

cake (brownies, sponge cake, and pudding with Cool Whip separating each

layer). Almost immediately upon out arrival at Maru’s aunt’s house at

a military base in Virginia, she laid out a massive Samoan-themed feast,

and Maru insisted I sit at the head of the table. EGG ROLLS

chicken wings, coleslaw, two whole fish, steak, corn, boiled shrimp, a

vanilla sponge cake and a two-foot tall bowl of layered triple chocolate

cake (brownies, sponge cake, and pudding with Cool Whip separating each

layer). Almost immediately upon out arrival at Maru’s aunt’s house at

a military base in Virginia, she laid out a massive Samoan-themed feast,

and Maru insisted I sit at the head of the table.

“Bruddah Josh is a sumo

wrestler,” Maru told his aunt, “He just don’t look it yet.”

I gained twelve pounds in the space of an afternoon. After two hours

of eating, Maru leaned forward and looked at me solemnly for a moment

before telling me that he wanted to show me some advanced sumo techniques.

He noted that no matter how much I ate, I wasn’t going to gain 200

pounds in five days. I was going to be competing against “big boys”

at the U.S. Open. It was time to take my sumo to the next level.

Maru shouted an order at his hairdresser, who leapt to his feet.

The champion pushed himself up and explained that there was a move

a small guy could use to beat someone much larger. Under Maru’s

direction, the hairdresser grabbed the back of Maru’s shorts and

demonstrated how to trip him through an ingenious twist of the hip.

It was a revelation.

Then Maru ordered me to go to sleep. He told me it was the best way to

turn food into fat. His aunt pointed me into a bedroom accented with pictures

of vivid blue waves and white sand beaches. My belly ached, but I was

giddy. I felt like I had been initiated into a secret language, the language

of weight. I eventually fell asleep and dreamed of giant, cresting waves

of Cool Whip.

A LARGE CROWD of people is struggling to get into the ballroom

at the New Otani Hotel & Garden in downtown Los Angeles. The U.S. Sumo

Open has already sold out, and the chandeliered ballroom is packed with

more than 800 people. Some stand shoulder to shoulder against the walls

or squat in the gaps between seating areas. Maru sits directly in front

of the sumo ring and is the only person who has a little space to himself.

I’m not feeling so good. For the first time, I’m wearing the

mawashi with nothing underneath and everyone can see my ass. Plus, I’ve

had nightmares about it falling off, so I tied it too tight and now it’s

crushing my balls and making me nauseous. I try to nonchalantly pull it

down a bit, but can’t bring myself to fidget with my crotch in front of

so many people.

There are twenty-three competitors, seven of them in the

lightweight division, and the program for the event details an intimidating

list of accomplishments beside each man’s picture. Most of the lightweights

are near the 187-pound limit, and almost all of them have won medals at

previous competitions. The list of accomplishments beside my picture is

blank. I am also the only one in the photos wearing glasses.

But the picture

was taken a month ago, and I’m a better wrestler now. I’m bigger too;

I’m up to 134 pounds and, most important, I feel substantially larger.

The one thing I haven’t learned is how to stay calm during a major sumo

tournament.

To be honest, I am scared. The other competitors milling around

are huge, and nobody’s smiling. It’s no fun to be in a room with twenty-two

diaper-clad men who want to kill you. I can feel my fighting spirit slipping.

I want to go home, but when my name is called, I lope up to the ring.

My lightweight matches go by in a blur of limbs and heavy impacts.

I know I’ve lost my cool I’m leaping off the start each time and

extending my center of gravity. My opponents (a Mongolian, a lawyer,

a UCLA student) sense that I’m not grounded. They come at me low

and repeatedly drive me backwards and out of the ring. I need to

relax, get low and feel my weight.

With each match, I gain a measure of confidence and by the time

I am called to the ring to for the open weight division, I’m calm.

“Stop leaping,”

Maru quietly insists. “And do how I taught you now.” I nod and step into

the ring.

Marcus Barber, my 460-pound opponent, looks like an avalanche waiting

to happen. The referee bows slightly, and we prepare to attack.

But at the go, I dodge his massive, flailing arms, and latch on

to the back of his diaper like Maru taught me. I’ve made it. Barber

is momentarily stunned that I have the advantage. The audience goes

crazy.

I stick my

leg forward and pull as hard as I can on Barber’s backside. In theory,

this is the point when he is supposed to stumble forward and trip over

my outstretched leg. I would then humbly bow and accept victory.

But he doesn’t budge. I pull again and feel panic rising in me.

I can’t move him. As his arms strain to reach my diaper, I try pulling

myself into a defensive position behind him. It doesn’t work. He

latches on to the diaper, heaves me into the air and gently carries

me out of the ring.

“You put up a good fight for a little guy,” he says.

Immediately after

the tournament ends, an 8-year old boy and his father approach me. The

boy asks me to sign his program. I laugh, thinking it’s a joke. I bitterly

ask the kid why he wants my autograph and he looks nervously at his shoes.

“Because you had the most fighting spirit,” his father says. “You should

have given up but you didn’t and that meant a lot to my son.”

In the next

ten minutes, a half-dozen people ask for my autograph, and it slowly dawns

on me that I’ve come a long way from when I weighed 128 pounds. I may

not be fluent in the language of weight yet but I can definitely hold

a conversation.

At one point, Maru looks up from his own, much larger

mob of autograph seekers and waves me over.

“Bruddah Josh,” he says. “You

fought hard. We just gotta get you a little fatter.”

|

|

|

|

Dohyo

(ring): The California

Sumo Association sells portable rings: large square

plastic mats that come with strips of foam attached

to form the raised edges of the classic fifteen-foot-diameter

dohyo. Starts at $3500.

Mawashi (diaper): Idaho-based Blackfoot

Canvas Co. has diversified its tepee business and now

makes a line of canvas diapers for the discerning wrestler.

$37 to $76; blackfootcanvas@hotmail.com.

To tie one, you'll need a friend and some instructions.

Try www.e-sanpuku.co.jp.

The Rules: Sumo is very simple. Push your opponent out of the ring or make him touch the ground with anything other than his feet and you win. There's one other way to win if you pick up your opponent and walk | out of the ring with him in your control, you are the victor even though you stepped out first.No eye gouging, closed-fist punches, groin hits, hair pulling, or kicking. Full-force face slapping is allowed in professional sumo but not in amateur, so you'll have to go to Japan if you want to be bitch-slapped by a 500-pounder.

Solo Sumo Training: Believe it or not, you can practice alone. In Japan wrestlers spend hours slamming into a thick wooden pole called a teppo. But in lieu of an official sumo pole, just about any pillar will do, as will, say, the corner of an office building. Simply squat low, slide your right foot forward, partially extend your right arm, and crush the palm of your hand into the wall with a guttural scream. This strengthens the wrist and teaches aspirants to hit hard. It also helps relieve tension.

|

|

|

|

|